|

Frans Hals The Laughing Cavalier 1624 Oil on canvas 86 x 69 cm The Wallace Collection, London  |

Finest Works of World Art

|

Frans Hals The Laughing Cavalier 1624 Oil on canvas 86 x 69 cm The Wallace Collection, London  |

|

Hieronymous Bosch (c. 1450-1516) Garden of Earthly Delights Right wing, "Hell" c. 1504 Triptych, plus shutters Oil on panel Central panel, 220 x 195 cm; Wings, 220 x 97 cm Museo del Prado, Madrid Hieronymous Bosch produced some of the most inventive fantasy paintings that have ever existed. His obsessive and nightmarish vision has its antecedents in the Gothic twilight world of the late Middle Ages and, although the allegorical medieval world view is now lost, there have been many recent attempts to 'read' his pictures, not least by those who have attempted to interpret Bosch by dream analysis

|

|

RUBENS, Peter Paul The Garden of Love c. 1630-32 Oil on canvas 78 x 111 3/8 in. (198 x 283 cm) Prado, Madrid Before Rubens, no Western artist of equally great talent had been as well born, as well educated, as well mothered, as well placed, or as widely and powerfully patronized. His father, a Protestant lawyer, left Antwerp for Westphalia to escape persecution This painter possessed of protean gifts proved to be an effective ambassador, scholar, courtier, humanist, lover and family man, classicist, architect, knight, numismatist, collector of antiquities, print designer, agent-connoisseur-adviser, pageant master, and fervent Roman Catholic. Equipped with rare energy, he would be up by 4:00 A.M. and could paint while dictating a letter and carrying on a conversation with a visitor, all at the same time. The artist was blessed with rare gifts of organization and a sense for realism and idealism. Rubens's creative, inventive response to conservative theology and to classical values validated the vast pictorial cycles demanded by his patrons. |

|

VELAZQUEZ, Diego Las Meninas 1656 Oil on canvas 10'5" x 9'1" Museo del Prado, Madrid

|

|

Rembrandt van Rijn The return of the prodigal son c. 1662 Oil on canvas 262 x 206 cm The Hermitage, St. Petersburg Rembrandt worked in complex layers, building up a picture from the back to the front with delicate glazes that allowed light actually to permeate his backgrounds and reflect off the white underpainting, and generously applied bodycolors which mimicked the effect of solid bodies in space. Never before had a painter taken such a purely sensuous interest and delight in the physical qualities of his medium, nor granted it a greater measure of independence from the image  |

|

|

|

GAINSBOROUGH, Thomas The Blue Boy c. 1770 Oil on canvas 70 x 48 in. (177.8 x 112.1 cm) The Huntington Art Collections, San Marino, California

|

"About

Modern Art", by David Sylvester

|

GOYA, Francisco The Shootings of May Third 1808 1814 Oil on canvas 104 3/4 x 136 in. Museo del Prado, Madrid Goya uses every pretext to present his figures, not as articulated bodies, but as looming shapes, which are as eloquent in their silhouettes as they are mysterious in their identity and often their actions. There are those menacing silhouettes of shadowy figures which - especially in the prints - loom up in his backgrounds. Goya's space is a lifeless void; the figures float because they have no density. All his figures are weightless: their feet placed on the ground, they do not so much stand on it as brush it, like marionettes. The space is like space in dreams, the figures like figures in dreams. The fantastic scenes become nightmarish because they have the quality, the atmosphere, of dreams |

|

Whistler, James Abbott McNeill Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Painter's Mother known as "Whistler's Mother" 1871 Oil on canvas 56 3/4 x 64 in. (144.3 x 162.5 cm) Musee d'Orsay, Paris |

|

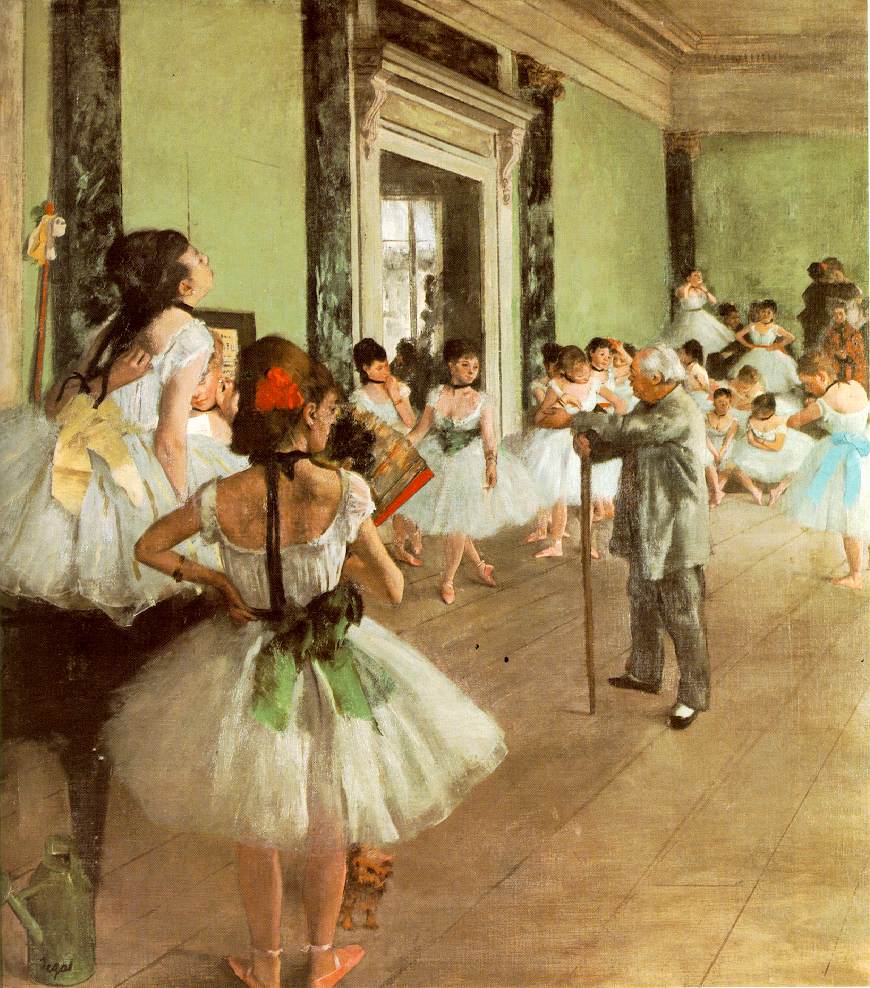

Degas, Edgar La classe de danse (The Dancing class) c. 1873-75 Oil on canvas 33 1/2 x 29 1/2 in. (85 x 75 cm) Musee d'Orsay, Paris  |